"Degenerate Music - a detailed statement by State Secretary Dr. Hans Severus Ziegler, general manager of the German National Theater in Weimar."

The Kampfbund für deutsche Kultur (KfDK, or Fighting League for German Culture) was founded in 1929 by Alfred Rosenberg, with the aim of promoting German culture while fighting the cultural threat of liberalism. Ironically, this organisation – best known for disrupting concerts and music classes, insulting and threatening artists, and distributing inflammatory and anti-Semitic pamphlets – was originally aimed at the nation’s elite. Hitler and other early Nazi leaders were searching for a way beyond mob-style violence, and decided to create a cultural organisation as a way to court the intelligentsia.

During the first years of its existence, the relatively small and regionally-organised KfdK attracted many intellectuals and, increasingly, musicians. With its conservative agenda of fighting ‘degenerative Jewish and Negro’ influences, it spent much energy promoting the ‘cleansing’ of museums, university faculties, and concert programmes of unwanted artists. In general, the KfdK appealed to radical nationalists and anti-Semites, to those who felt betrayed by defeat in World War I and by the Treaty of Versailles, and to those who felt outraged by the leftist, modernising and ‘cosmopolitan’ tendencies of the Weimar Republic.

The KfdK was initially not very aggressive, relying instead on lectures, intimidation and propaganda. After Hitler’s rise to power in 1933, it became increasingly violent, with the support of the Stormabteilung (SA, Storm Troopers, or brown shirts) changing both its techniques and its membership pool. The KfdK had its own orchestra, which was selected to perform a special concert for Hitler’s birthday. It also acquired control over the important music journal Die Musik, which gave it an official outlet for racist and nationalist opinions on music.

(http://holocaustmusic.ort.org/politics-and-propaganda/third-reich/kampfbund-fr-deutsch/)

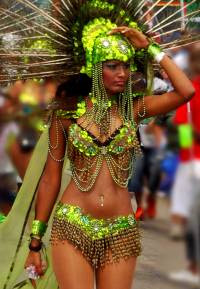

Centre Section of the triptych Grosstadt, 1927-8, by Otto Dix (1891-1969). It is an evocation of the Gershwin (1898-1937) period - the Jazz Age. This age and the kind of music (Jazz) were condemned by the Nazis as decadent and racially degenerate

Indeed, the Nazis were so fearful of African and African-American culture (particularly jazz) that in 1930 a law was passed that was titled "Against Negro Culture." In other words, the Nazis were clearly aware of the potential for popular cultural forms to taint what they considered to be genuine Aryan culture—whether this taint was a result of marriage or of music. As a consequence, the Germans often conflated stereotypes of African-American musical performers with those of Jews and Africans into some of their most heinous propaganda pieces.

Two of the most infamous and well-known Nazi propaganda artworks were posters which advertised cultural events. In a poster advertising an exhibition of entartete musik (degenerate music), for example, the viewer is confronted with a dark-skinned man in a top hat with a large gold earring in his ear.

This distorted caricature of an African homosexual male in black face playing a saxophone has a Star of David clearly emblazoned on his lapel. To the National Socialists, the most polluting elements of modern culture were represented by this single individual. They were suggesting that anyone who listened to jazz (or enjoyed other forms of art that they judged to be degenerate) could be transformed into such a barbarous figure.

Nazi propaganda poster titled "LIBERATORS" that epitomizes many perennially-recurring themes of anti-Americanism, by the Dutch SS-Storm magazine that then belonged to a radical SS wing of the National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands (1944)

Toward the end of the war, the Nazis circulated posters in a somewhat desperate attempt to get their "white European brothers" to join their cause. In one infamous poster, the designer depicted a multi-armed monster clutching two white American women. Attached to his muscle-bound body are iconic references to the Ku Klux Klan, Judaism (the Star of David), boxing gloves, jazz dancing, and a lynching noose. At his middle is a sign that reads in English "Jitterbug—the Triumph of Civilization." This poster was directed at white European men, and it urged them to protect their wives and their culture against a coming invasion of primitive, inferior American men. As occurred in the poster that warned against jazz, this image conflated stereotypes of the Jew with that of the African in an attempt to frighten white (Aryan) Europe and America into joining their cause. The exaggerated racist stereotypes served to strengthen and amplify widely accepted attitudes regarding racial and ethnic superiority. With these images, the National Socialists were offering their justifications as to why certain groups should be feared and thus eliminated.

(http://www.enotes.com/genocide-encyclopedia/art-propaganda)