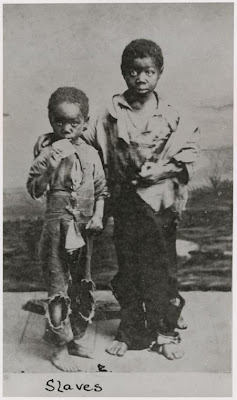

The Antebellum Slave Trade in Regional and Historical Perspective

From HNet Calvin Schermerhor writes: Robert Gudmestad has made at least two important contributions in A Troublesome Commerce. The first is to account for regional differences in perceptions of the antebellum interstate slave trade, and the second is to account for why southerners accepted the trade while simultaneously maintaining ambivalence toward traders. Gudmestad argues that by the mid-1830s, white southerners came to view the long-distance domestic slave trade as necessary to southern society rather than as an embarrassing practice that tore apart enslaved families, corrupted the morals of slaveholders, and flooded the Lower South with potentially seditious slaves. Gudmestad orients his reader to think of the interstate slave trade in terms of regional capitalist-economic development and explores its social ramifications.

Robert H. Gudmestad. A Troublesome Commerce: The Transformation of the Interstate Slave Trade. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2004

A Troublesome Commerce therefore adds to an historiography that includes Steven Deyle's Carry Me Back: The Domestic Slave Trade in American Life (2005), Walter Johnson's Soul By Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market (1999), and Michael Tadman's Speculators and Slaves: Masters, Traders, and Slaves in the Old South (1989).

Gudmestad investigates the perceptions and practices of the speculator or trader as a way to connect slavery's economic expansion with its social significance. In contrast to a slaveholder who may have bought or sold slaves locally and for a variety of reasons, traders earned a living primarily by purchasing enslaved people from slaveholders in the Upper South and selling them to buyers in the Lower South. In the popular imagination, according to Gudmestad, "The trader broke up families, emphasized profit above piety, manipulated reality, and ruined paternalism. The stereotype had all the qualities that slaveowners were supposed to control" (p. 190). Gudmestad argues that "when [the slaveholder] could not meet this idea, the speculator was one way to explain their failure.... [slaveholders] blamed all others--banks, debt, abolitionists, the slaves themselves--for the slave trade because to admit their own culpability would have undermined the whole basis of their society" (p. 190). The idea that slaves represented cash above any supposed membership in a slaveholder's extended family upset southerners and inspired reactions, from moral outrage to regulatory legislation. In response, traders joined southern politicians and other proslavery apologists to sanitize the image of the slave trade so that by the mid-1830s, southerners could defend slavery and slave trading in the same breath. Gudmestad argues compellingly that southerners ended up agreeing to ignore the realities of speculation in the interstate slave trade in order to preserve the social order it supported.

Issac Franklin watching slave caravans moving from the upper south to the lower south.

By the early nineteenth century the interstate slave trade developed in reaction to regional settlement in the southwest. Gudmestad contends that speculation "was sporadic and uncertain at a time before there was a crush of labor in the Old Southwest" (p. 17). Profits from the production of cotton and other commodities attracted settlers. Planters in the Lower South states of Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, and Louisiana increased demand for enslaved laborers, whom Gudmestad refers to most often as "bondservants" (p. 48, passim). Initially, planters moving to the cotton frontier forcibly transported slaves with them, but as white migration fell and established slaveholders sought to expand their holdings, more and more enslaved people were marched or shipped south in the interstate trade. "Rather than being relatively stable in the nineteenth century," Gudmestad argues, "the interstate slave trade increased in volume and proportion during the 1820s and 1830s as white migration declined and the demand for labor increased in the Lower South" (p. 20). Southern economic development and consequent demographic changes stand in the background in Gudmestad's narrative of what white southerners made of speculators' activities.

Slave auction.

-

According to Gudmestad, the activities of speculators inspired resistance among potential victims of the trade and initially alarmed legislators in the nation's capital. In 1816, after a slave named Anna jumped from a third story window to avoid being sold away from her husband and children--shattering her arms and breaking her back--an outraged John Randolph of Virginia moved to regulate the slave trade in the District of Columbia. The measure failed, but his efforts represented the problems slave traders posed to white southerners' perceptions of slavery: the cash traders so prominently featured in advertisements belied an organic relationship between master and slave. "The irony," according to Gudmestad, "is that a business that labored mightily to reduce slaves to just another commodity accidentally promoted the fact of bondservants' humanity" (p. 48). In the 1810s and 1820s, men like Randolph anguished over what the slave trade did to the humanity of slaves and masters.

Gudmestad explains regional differences regarding views of the slave trade by the 1820s: whites in the Upper South who were troubled by the effects of slave sales on the morals of masters, and whites in the Lower South who feared that their part of the country was becoming a dumping ground for rebellious slaves. "When southerners looked at the white image in the white mind," he contends, "they did not like what they saw" (p. 63). The dilemma confronting slaveholders in the Upper South concerned how to rationalize selling enslaved people away from their families to traders likely to transport them out of state. While many slaveholders tried to keep families together--or at least proffered that aim--the interstate trade tore families apart. Buyers in the Lower South, by and large, wanted individual laborers and not families. Observers in the Upper South who worried about the potential threats posed by a surplus slave population began to see the trade as a practical alternative to colonization. Evangelical Protestants, meanwhile, turned churches into the "'bulwark'" of slavery, at least in the minds of many abolitionists (p. 143). Gudmestad contends that churches solved the moral dilemma regarding the slave trade by shifting from opposition to noninterference in individual slaveholders' affairs. "By 1840 then," according to Gudmestad, "most southern evangelicals accepted the slave trade as a regular and necessary part of southern society" (p. 146). Ironically, the moral dilemmas slaveholders faced ended up strengthening slavery since slaveholders convinced themselves that they had no option but to sell slaves to traders. Perceived economic necessity became a solvent for moral guilt, as the interstate trade became an increasingly common and seemingly inescapable part of Upper South slavery by the mid-1830s.

Citizens in the Lower South were not concerned about the moral health of masters and did not wait for religious leaders to come around to their position. Gudmestad contends, "residents there generally accepted the interstate slave trade--even with all its flaws--because of its importance in replenishing and augmenting the labor supply" (p. 95). Especially following the Turner Rebellion of 1831, Mississippi and Louisiana attempted to regulate traders' activities lest slaves become infected with the "contagion of rebellion" (pp. 104-105). Interstate slave traders found creative ways to evade restrictions on slave imports. If observers in the Upper South worried about moral decay among the slaveholding classes, whites in the Lower South worried about rebellion sweeping the country.

Slave Auction.

Separation of families at slave auctions.

The slave sale.

Interior of a slave jail.

Attitudes toward the trade in the Upper South caught up to those in the Lower South, and by the 1830s, "slave traders became a species of social workers who redeemed the dregs of society" (p. 171). Slave traders, who had been implicated in kidnappings, sexual abuse, and clandestinely dumping the bodies of dead slaves, used a variety of techniques to improve their image, including moving slave jails and auctions out of public view, keeping secret the details of their activities, and marching coffles of slaves out of cities under the cover of darkness. While abolitionists worked to publicize the terrors of family separation and the horrors of transportation at the hands of traders, traders represented themselves as respectable businessmen, which in Gudmestad's view "helped effect a change in opinions towards speculation from initial skepticism to grudging acceptance" (p. 164). Southern whites reacted to abolitionist criticisms by blaming the messenger and excusing slave traders for breaking up slave families. When southerners defended slavery, therefore, they had to defend traders' activities as well. At the issue's core, however, was the realization that there was little anyone could do to stem the interstate slave trade. Gudmestad concludes that "moralizing proved ineffective in blunting the force of economic and social considerations" (p. 177).

Slave traders Isaac Franklin and John Armfield office in Alexandria, Virginia.