Out of a swampy thicket, near the blue waters of Long Island Sound, 200 old men, women and children stepped into the bright sunshine and entered a new world.

Hundreds of edgy soldiers, mustered from villages and farms across Connecticut, had finally surrounded the Pequots and their leader, Sassacus.

It was July 13, 1637, a critical day in the Pequot War that had consumed Puritan Connecticut for several years. Six weeks before, in a key victory for the colonists, Capt. John Mason had led a massacre at the Pequot fort in Mystic, killing as many as 700 Indians in a single hour.

attack on the Pequot fort at Mystic

This summer afternoon was a jubilant one for the Puritans and their Mohegan scouts who had cornered these "most terrible" Pequots. A new chapter in American history was about to begin: Indian enslavement in Colonial America.

Among the Pequots caught in the bog in what's now part of Fairfield, a group of perhaps 17, mostly children, were thought to have been exported as slaves. Others were handed out to soldiers as wartime booty. Historians believe these 17 Pequots later ended up on an island off Nicaragua. Like many of the Indian slaves sent from America over the next century, there is little record of what happened to them.

Barely five years after their first recorded contact with Europeans, this final battle of the bloody Pequot War conclusively finished a doomed experiment by Indians and Puritans to live side by side. By the time the Treaty of Hartford was signed the following September, formally ending the war, the English had killed or enslaved more than 1,500 Pequot men, women and children, scholars believe.

During the uneasy decades that followed, as the Puritans pushed deeper into Indian country and their numbers swelled, it was difficult to travel through Connecticut, Massachusetts or Rhode Island and not encounter an Indian slave, working in a field, orchard or boatyard.

By the end of the 1600s, there were probably thousands of Indian slaves, many of them servants in homes and on farms. It would become, in the words of Roger Williams, a founder of Brown University, an essential component of "the Unnecessary Warrs and cruell Destructions of the Indians in New England."

In Connecticut and throughout New England, where, 350 years later, descendants of Indians and Europeans still have an uneasy relationship, Indian slavery remains a rarely recited part of our history.

Wampanoag, longhouse

"There are a lot of things that people in America don't have any idea about,"' said Everett "Tall Oak" Weeden, an Indian historian who shares both Pequot and Wampanoag ancestry. "History has been sanitized."

The Indians `have their eyes fixed upon us'

A primal fear of Indians, a desperate shortage of labor, a biblical sense of entitlement - these forces coalesced, leading to the enslavement of the Native Americans in southern New England in the 1600s. The colonists ultimately thought of the conflict as the "civilized" English against the "savage" natives.

"Partly it's social control. But they also want the labor. People wanted household servants," said Margaret Newell, a professor at Ohio State University who is writing a book on Indian slavery.

In Rhode Island and Massachusetts, and to a lesser extent in Connecticut, Newell said, "You would find [Indian] women working as domestic servants, taking care of children. You would find men working as farm laborers, drivers. You would find children taking care of livestock."

For some Indians, servitude lasted only until age 24. But others were bound to masters for indefinite periods. Indian slaves and household servants appear on census rolls and court records well into the 18th century.

This was a time of growing divisions and bloody violence between the native populations and the Puritans. As the colonists sought to settle in to their new home in America, there were conflicts, small and large, all over. It was a time of murdered women and children, of severed limbs and smashed corpses, when it was not uncommon to see Indian and English heads mounted on stakes, wigwams burned and frontier farms devastated.

For many Indians, Mason's brutal Pequot massacre and others after it remained fresh. For the colonists, the scalpings and mutilations, which included flayings and torture, seemed too monstrous for any true Englishman to ever accept.

By the beginning of King Philip's War in 1675, when Indians attacked and destroyed town after town in New England, it would be difficult to overestimate the fear English colonists felt as they sought to conquer and subdue New England. After a string of stunningly successful Indian attacks at the start of the conflict, Puritans were well aware that "all the Indians have their eyes fixed upon us."

Thousands of English and Indians would perish in the bloody two-year conflict, named for a regal Wampanoag sachem, or chief, whose father, Massasoit, sat with the Pilgrims at the first Thanksgiving feast. By the end of 1675, it was full-scale battle across New England.

"Many of our miserable inhabitants lye naked, wallowing in their blood, and crying, and whilst the Barbarous enraged Natives, from one part of the Country to another are in Fire, flaming their fury, Spoiling Cattle and Corn and burning Houses and torturing Men, Women and Children," wrote one unidentified colonist, quoted in historian Jill Lepore's revealing 1998 book, "The Name of War."

The Indian threat "strained even the most eloquent colonists' powers of description," Lepore writes of a time early in the war when Indians nearly drove the Puritans from New England's interior.

"I was so struck by how strident and how fearful these people were," University of Connecticut anthropologist Kevin McBride said of his research into Indians and Puritans of the 1600s. "These guys must have been panicked."

Enslaving the problems

As the 17th century wore on, and colonists grew to outnumber natives in New England by about 2 to 1, Indians were increasingly pursued. A systematic divvying up of captives from the many Connecticut tribes emerged. The colonists originally focused on the more warlike Pequots, but soon members of the Narragansetts, Nipmucks and Wampanoags were also enslaved.

"The general court appointed certain persons in each county to receive and distribute these Indian children proportionately, and to see that they were sold to good families," wrote Almon W. Lauber in his 1913 book, "Indian Slavery in Colonial Times."

"The custom of enslavement came from the necessity of disposing of war captives, from the greed of traders and from the demand for labor," explained Lauber, whose book is still considered an essential reference.

Captured Indian warriors were frequently executed - or shipped to slave markets around the world. By the time King Philip's War began, Indian slaves, often women and children, were a common sight across southern New England.

From Newport, R.I., to Portsmouth, N.H., Indians came to public auction, "tied neck to neck," and sold for half of what an African might bring.

A 7-year-old girl was toted to Connecticut from a battle in Massachusetts, a spoil of war who was handy around the house. At times, there were so many captured Indians available that a few bushels of corn or 100 pounds of wool sufficed for payment. A New London man left "an Indian maidservant" as part of his estate. Another, a farmer and businessman from the New London area, kept a careful diary noting how common Indian slaves were on the farms and in the homes of southeastern Connecticut.

And on sailing ships, bound for the slave markets in Europe, Africa, the Caribbean and the Azores, Indians were packed away tightly by the profiteers, who kidnapped or bought them wholesale from Colonial authorities eager to finance an increasingly costly war against the Indians.

Indians who surrendered were treated only slightly more gently in the colony, with the Connecticut General Court ordering children sold as indentured servants for 10-year terms, though some would be slaves far longer if they got into legal trouble in Puritan courts.

A note left by attacking Nipmuck Indians after the plundering of Medfield, Mass., in February 1676 reveals much about the time: "We have nothing but our lives to loose but thou has many fair houses and cattell & much good things."

The rewards of war

In the fall of 1676 the sailing ship Seaflower departed Boston Harbor for the Caribbean, its cargo hold filled with nearly 200 "heathen Malefactors men, women and children" sentenced to "Perpetuall Servitude & slavery."

As Lepore recounts in her book - one of the few published scholarly examinations of Indian slavery - the sale and lucrative export of Indians had become by 1676 one of "the rewards of war" that replenished "coffers emptied by wartime expenses." Despite government efforts to regulate it, much of the trade was conducted illegally and ruthlessly.

The slave export began to heat up in 1675 and 1676, when captives from the rapidly expanding King Philip's War were filling New England cities, further frightening the English. Most of the Indians captured and exported out of New England were from Massachusetts, whose towns suffered the most from Indian attacks.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the colonists also found that adult Indian males who were kept as slaves made poor servants here. Mason said as much, when he wrote of captives from the Pequot War: "They could not endure that Yoke; few of them continuing any considerable time with their masters."

African-Indian intermarriage

Records of Indian slaves turn up well into the 18th century, but the practice faded rapidly in the 1700s, because of a growing market for African slaves and the widespread elimination of Indians and their culture. Scholars like Lepore also said that New England at this time began to see itself as a place that celebrated liberty and a growing anti-slavery movement.

Meanwhile, the eradication of Indian males through war, ravaging diseases and slavery led to significant intermarriage between native women and African males in the 18th century and beyond. Thus, as researchers like McBride and Newell note, the arrival of African slaves would help assure the survival of some Indian communities into the 21st century - while also setting the stage for some of the racial tension today.

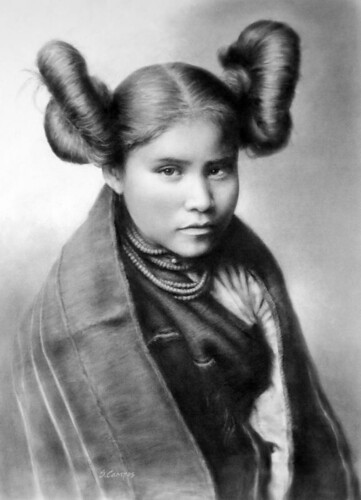

Narragansett woman dressed up for a powwow

Narragansett woman dressed up for a powwow

"Slavery really did have a devastating impact on the Native American population. Men were more likely to be exported. You had some tribes and populations where the ratio of women to men is completely out of whack," said Newell.

In the 20th century this would lead to tribes, such as the Narragansett and Pequots, with members who, to an outsider, look distinctly African American - but who nevertheless descend from historic New England tribes.

For many modern Indians in southern New England, slavery remains an essential and too-little-discussed element of their being, a chapter that must be acknowledged to understand the dynamics of today's often fragile relationship between Indians and non-Indians.

Back to the past

This year, on the 365th anniversary of the Fairfield "swamp fight" of 1637, "Tall Oak" Weeden and a delegation of Wampanoag Indians and Mashantucket Pequots went hunting for remnants of this forgotten slavery era.

Searching for clues, they traveled to St. David's Island in Bermuda. There they met with a small clan claiming to be descendants of New England Indian slaves shipped there centuries ago. Those who went came away convinced they had struck gold when they saw the faces, the dances and rituals of the St. David's Indians.

"I was struck by how much they looked like us," said Michael J. Thomas, a Mashantucket tribal leader who went on the Bermuda trip this past summer.

According to local legend, the wife and son of King Philip might have been among those on St. David's. After the king's death, his wife, Wootonekanuske, is said to have married an African man, preserving a genealogical line with Indians in New England.

The Pequots, flush with casino wealth and in the midst of their own 21st century resurgence, plan to dig even further into slavery's hidden history, Thomas said.

"What's to be learned is a more accurate perception of Colonial-era history," he said. "It helps people to understand our insecurities of today."

Mission San Carlos Borromeo in the Monterey

Mission San Carlos Borromeo in the Monterey

As we have taken into our national family seven millions of Negroes, and as we receive foreigners at the rate of more than five hundred thousand a year, and assimilate them, it would seem that the time may have arrived when we can very properly make at least the attempt to assimilate our two hundred and fifty thousand Indians, using this proven potent line, and see if that will not end this vexed question and remove them from public attention, where they occupy so much more space than they are entitled to either by numbers or worth.

As we have taken into our national family seven millions of Negroes, and as we receive foreigners at the rate of more than five hundred thousand a year, and assimilate them, it would seem that the time may have arrived when we can very properly make at least the attempt to assimilate our two hundred and fifty thousand Indians, using this proven potent line, and see if that will not end this vexed question and remove them from public attention, where they occupy so much more space than they are entitled to either by numbers or worth.