The New York Times reports: "Carnival’s Louder Commercial Beat Adds Dissonance," by John Eligon, 9 March 2011:

PORT-OF-SPAIN, Trinidad and Tobago — To some people here, Dean Ackin, 38, with his boyish face, is an inspiration of entrepreneurship, a bearer of this country’s evolving culture. To others, he is a threat to this nation’s most beloved social and cultural treasure: Carnival.

Mr. Ackin runs one of the country’s most popular Carnival bands, the groups of people who don costumes and masquerade — or play Mas, as locals call it — in the raucous annual two-day street parade. The roughly 5,000 spots available in Mr. Ackin’s band, Tribe, sell out every year almost as fast as they go on sale. Demand has been so high since he started Tribe in 2005 that Mr. Ackin just started a second band.

But some say Mr. Ackin and others like him, who have in recent years spun profitable, year-round businesses out of organizing these bands, threaten the existence of Carnival as Trinidadians know it.

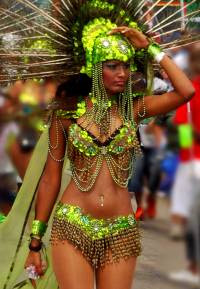

By shunning the conservative, traditional costumes for cheaper, skimpier outfits that are sometimes produced outside of Trinidad, these new bands, critics say, are distorting their forebears’ creation and sending work elsewhere at a time when the government and others are trying to turn Trinidadian-style Carnival into a more profitable and exportable industry.

“We call it two-piece and fries, the bikini and the bras,” said Stephen Derek, a traditional costume maker, referring to the skimpy costumes that have become a staple of the new bands. “The costume comes like a fast food. To them, the bottom line is profit. It has nothing to do about country or culture anymore.”

The entrepreneurial bandleaders counter that they are part of a natural evolution, merely offering what people want.

“If you really look at those people who play Mas with the younger bands, or if you talk to a visitor abroad and say: ‘Hey, have you ever heard of Trinidad Carnival? What band would you play with?’ they would call Tribe or they would call one of the younger bands,” Mr. Ackin said. “That says we are reaching out further than the traditional bands. We are reaching out to the international market.”

With few exceptions, the 1.3 million people living on these twin West Indian islands believe that they do Carnival better than anyone in the world. But the generational clash has raised questions over how today’s Carnival is shaping the country.

Is the reliance on mass-produced bikinis — a far cry from the elaborate, hand-crafted costumes Trinidadians had grown accustomed to — stifling the creative works that have been the hallmark of traditional Carnival, which the government of Prime Minister Kamla Persad-Bissessar has been pressing to revive since she took office last year?

Or does it reflect the country’s new energy, representative of a push beyond Trinidad’s reputation for complacency in developing revenue streams beyond oil production?

Carnival festivities here begin in earnest right after Christmas, but the signature parade was held on Monday and Tuesday, right before Ash Wednesday, adhering to the Catholic tradition of one final period of revelry before the start of Lent.

The tradition here started with the island’s 19th-century slave masters, and was carried on by the African slaves after they were freed in 1834. To make the custom their own, former slaves took to burning sugar cane, to symbolize their freedom from the plantations here, and in later years residents began wearing costumes that both portrayed folkloric characters from Africa and mimicked their colonizers.

Now the event attracts about 40,000 visitors to Trinidad annually, nearly half of them from the United States. In parades held throughout the country, as many as 300,000 people march around trucks blasting Soca music, according to government estimates. Estimates of the economic windfall from Carnival vary widely, from just over $27 million to hundreds of millions.

What distinguishes Carnival here is an emphasis on getting people — even tourists — to purchase a costume from a band for as little as $200 and march. Several bands like Tribe have taken it a step further, charging $400 to $1,000 for a whirlwind experience that includes an open bar for both days, meals, security and shuttle service.

Mr. Ackin said that Tribe, which has around 5,000 masqueraders each year, usually has a waiting list 2,000 people long. Several celebrities have also marched with Tribe, including the actor Idris Elba an the billionaire Richard Branson.

His new band, Bliss, had just over 2,000 masqueraders this year and a long waiting list as well, he said. Over all, the market to pay hundreds of dollars to join a band, even in a tight economy, seems to be growing.

Mr. Ackin, who has emerged as a quasi-celebrity here, spent years working in a bank and running a women’s fashion boutique. But he and his wife, Monique, a co-bandleader, got into the Carnival business by creating a band in 2000 for J’Ouvert, the early-morning parade that kicks off Carnival. His company now organizes five parties around Carnival time here. It also organizes parties at Carnivals in Miami, Washington and London.

The transformation of Carnival bands into businesses has disrupted the social order in which bands used to consist of friends getting together to hang out, make costumes, and eat and drink together, traditionalists said.

“The designers or the bandleaders of those other bands call themselves designers and artists, but I think that is fraud,” said Brian MacFarlane, whose band won large band of the year in each of the previous four years. “If you really, truly are a designer and artist, you’d be holding true to the art form and the culture.”

Indeed, Trinidad’s Carnival has started to resemble that of “Brazil in a lot of ways,” said Winston Peters, the minister of arts and multiculturalism, “where you just have decorated bikinis and stuff with a headpiece. I can’t be against that because that’s what people want. At the same time, we don’t want the traditional Mas of our country to die.”

Perhaps the most contentious aspect of the bikini costumes is that many bands import some of them from China. Mr. Peters has proposed putting a 2,000 percent tax on imported costumes.

Mr. Ackin said that Tribe and Bliss imported about 20 percent of their costume pieces, a necessity to meet their demand and get high-quality production unavailable in Trinidad.

People on both sides of the argument seem to agree that Trinidad needs to better harness the skills of people in the Carnival business — from the artisans who make the costumes to the people who manage the bands — and the country’s resources to create an exportable industry.

The government is considering increasing the prize money for the bands with the best costumes, and it has started a band with which anyone can march in a homemade costume. Those efforts come after the creation of a Mas Academy that teaches and certifies people in Carnival trades.

Derrick Lewis, who, along with his brother Dane, started a wildly popular band, Island People, in 2005, said it was important to find ways to marry the traditional Carnival with the new.

“I think popular culture will become culture,” said Mr. Lewis, 52. “The same that happened with hip-hop. I’ve seen Kanye West performing with full orchestral violins and stuff like that. I think we need to encourage the fusion of the traditional and the contemporary.” (source: The New York Times, Vijai Singh contributed reporting.)

No comments:

Post a Comment