India welcomes three world-class coaches for its national teams

This article was first published on SLAMOnline.com on May 18th, 2011

If there’s one thing that you can say with complete surety about Indian culture is that we treat our guests with honor. As a child, when my family had visitors staying over and I refused to give up my bedroom for the guests, my mother would take me to a corner and repeat the old Indian proverb: “Mehmaan Bhagwan Saman Hai” – The Guest is like God.

Yes, guests in India are showered with presents, treated like royalty, and are force-fed meals until their stomachs churn (we consider this a good thing). Anyone who has ever been welcomed into an Indian household knows that, when it comes to food, ‘I’m full’ means ‘I could eat two more rotis, please,’ and a firm ‘No’ means, ‘Yes, I wouldn’t mind that last piece of Butter Chicken.’ From simple households to State Diplomats, the over-welcoming philosophy of the Indian people (mostly) remains.

And this is one of the major reasons why, despite all the teething troubles that have hampered the game of basketball in the past (rampant corruption at the state level, backward infrastructure, little cohesive organization, etc.) the game continues has continued to develop at a good pace. India has welcomed the world of basketball with open arms – from IMG Worldwide to the NBA – and in return, the world of basketball has invested wisely to the growth of the game in India. The welcoming attitude has worked well in our favor, as everything from infrastructure to personnel is now showing promise of progress.

And this is one of the major reasons why, despite all the teething troubles that have hampered the game of basketball in the past (rampant corruption at the state level, backward infrastructure, little cohesive organization, etc.) the game continues has continued to develop at a good pace. India has welcomed the world of basketball with open arms – from IMG Worldwide to the NBA – and in return, the world of basketball has invested wisely to the growth of the game in India. The welcoming attitude has worked well in our favor, as everything from infrastructure to personnel is now showing promise of progress.April in particular was especially big for the game in India. Geethu Anna Jose, the former captain of the Indian Women’s team, became the first Indian to get a tryout with the WNBA – she wasn’t accepted, but she left a good impression with the Chicago Sky, the L.A. Sparks, and the San Antonio Silver Stars. Meanwhile, Bucks’ point guard Brandon Jennings made a trip over to our shores, becoming the 16th NBA/WNBA player/legend to visit India over the past three years.

But the biggest piece of news was leaked out this week, as the Basketball Federation of India (BFI) announced that it hired three world-class coaches to lead the Indian Basketball Teams and further the BFI’s grassroots growth of the game in India.

Kenny Natt, who was interim head coach of the Sacramento Kings after the firing of Reggie Theus during the ‘08-09 season, has been brought on board to coach the Indian Senior National Men’s Basketball team. Natt was an assistant coach under Jerry Sloan with the Utah Jazz from 1995-2004, and was part of the team that twice reached the NBA Finals in 1997 and 1998. He then became an assistant coach with the Cleveland Cavaliers from 2004-2007, including the season when the LeBron James-led Cavs reached the NBA Finals.

Natt’s first job will be to work with Indian Men’s team at a camp in Delhi in preparation for the FIBA Asia Basketball Championship set to be held in Wuhan (China) in September. Natt will be taking over the reins of the Men’s team after Coach Bill Harris, formerly head coach of NCAA DIII side Wheaton College, who led the Indian team to the 2010 Asian Games in Guangzhou (China).

The Indian Senior Women’s National team will be headed by Pete Gaudet, a famous name amongst college instructors. Gaudet has been involved with college hoops for over 40 years, coaching both men’s and women’s basketball in the process, including holding positions at West Point, Duke, Vanderbilt and Ohio State. While at Duke (as mostly an assistant to Mike Krzyzewski), Gaudet won two NCAA Championships and made seven Final Fours, coaching eight All-Americans, three national players of the year, and 12 NBA draft picks.

Like Natt, Gaudet will also be preparing the Women’s side for the FIBA Asia Basketball Championship – the Women’s edition of this competition will be held in Omaru and Nagasaki in Japan at the end of August. Before Gaudet, the Indian Women’s side was coached by WNBA player Tamika Raymond at the 2010 Asian Games.

Like Natt, Gaudet will also be preparing the Women’s side for the FIBA Asia Basketball Championship – the Women’s edition of this competition will be held in Omaru and Nagasaki in Japan at the end of August. Before Gaudet, the Indian Women’s side was coached by WNBA player Tamika Raymond at the 2010 Asian Games.Lastly, the BFI brought in Zak Penwell as a Strength and Conditioning coach for the national sides in India, the first time that such an appointment has been made for the national level players in the country. In the past, the Indian national teams had been thoroughly exposed by several Asian opponents who were stronger, faster and more durable – even if the skill and talent level was closed, India lagged behind when it came to their physical fitness and performed poorly.

The last bit of news has been especially encouraging for top-level Indian players like Jose, who admitted that she struggled amongst the stronger American players during her WNBA tryouts. And now, with experienced NBA and college coaches being the guiding forces behind some of India’s brightest stars, expectations are high for the country to follow in China’s footsteps and play up to its potential – more than a sixth of the world’s population is over in India, and it is about time that the country ends its historic underperformance in most other sports excluding cricket.

Meanwhile, the other pieces to complete basketball’s jigsaw puzzle are shaping up nicely: Jose may not have qualified for the WNBA, but a tryout in itself was a major step forward. Youngsters have been encouraged by her success and are now confident that they can follow her footsteps to the world’s best leagues.

The biggest contribution comes by the hand of IMG-Worldwide, who in their partnership with India’s Reliance Industries is hell bent to change the face of the game – IMG-Reliance have been behind every major development for the BFI since 2010.

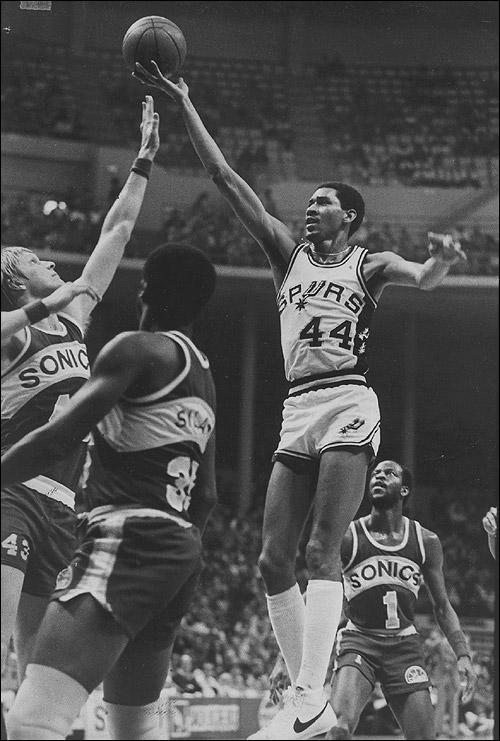

The NBA continues to put a lot of its time and effort in developing grassroots popularity of the game here: Dwight Howard, Pau Gasol, Brandon Jennings and George Gervin, to name a few, have carried the message of hoops to this cricket-crazy country over the last year. The NBA has held inner-city recreational leagues in five major cities around the country, and this year, introduced a Junior Skills Challenge to get the kids started early.

And then of course, there are the players themselves. More than ever, young players are taking basketball seriously as a career option and present stars are hopeful that they will one day participate in India’s own National Basketball League. The biggest (in size and potential) hope comes in the size-22 sneakers of Satnam Singh Bhamara, the 15-year-old, 7-2 inch giant with a rare combination of size and skill who is currently a student-athlete at the world-renowned IMG Academy in Bradenton, FL and is, as we called him on SLAMonline, the ‘Big Indian Basketball Hope.’

So yes, we’re ready to welcome the world of Basketball in India, bring it into our households, treat it with the respect that only a guest deserves, and make sure that we feed it until it’s full and then feed it a little more.

Is the world ready to welcome us?