Certain types of seashells have been used by natives as currency on every continent of the world except Antarctica. This Kikuyu woman is in traditional dress showing hundreds of Cowrie shells. (Photo: Flickr user wayfaring stranger.)

According to Ingrid Van Damme, a Member of the Museum staff of the National Bank of Belgium, "Cowry Shells, a trade currency": The Museum of the National Bank is probably not the first thing that crosses your mind when you are talking about shells. And yet, apart from a large number of coins and banknotes it also possesses a nice collection of primitive means of payments. Within this category of traditional money the cowry shell is one the most renowned representatives.

Cowrie shells, African ring money and ancient gold money

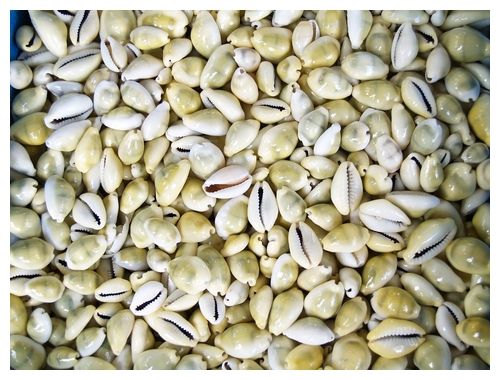

Long before our era the cowry shell was known as an instrument of payment and a symbol of wealth and power. This monetary usage continued until the 20th century. If we look a bit closer into these shells it is absolutely not astonishing that varieties as the cypraea moneta or cypraea annulus were beloved means of payments and eventually became in some cases huge competitors of metal currencies. All characteristics of money, i.e. durability, handiness or convenience, recognizability and divisibility are embodied in these small shells. In comparison with foodstuff or feathers which can fall prey to vermin, shells withstand easily frequent handling. They are small and very easy to transport and their alluring form and looks offer them a perfect protection against forgery. Besides, counting was not always absolutely necessary. As the shells almost all had the same shape and size weighing often sufficed to determine the value of a payment.

Cypraea moneta (cowrie).

According to local preferences and agreements, cowry shells could also been packed or stringed to larger unities. On the Bengalese market e.g. large payments were made in baskets full of cowries, each one containing approx. 12.000 shells. Due to it’s peculiar form the cowry was also considered to be a fertility symbol, which made it extremely popular with a number of peoples.

Gourd Ornament with Cowrie Shells

The cowry which is indigenious in the warm waters of the Indian and Pacific Oceans travelled by land and by sea and gradually spread out its realm. It became the most commonly used means of payment of the trading nations of the Old World. The cowry was accepted in large parts of Asia, Africa, Oceania and in some scattered places in Europe. Chinese bronze objects, the oldest dating back to the 13th century B.C., inform us about this monetary usage. This tradition has also left its traces in the written Chinese language. Simplified representations of the cowry are part of the characters for words with a strongly economic meaning, as e.g. money, coin, buy, value…

Cowry shell collecting and trading became a real industry on the Maldives. Both men and women were involved and had their own responsibilities. Women wove mats of the leaves of the coconut trees which were put on the watersurface. Little molluscs covered these mats but before they could be harvested the mats were left on the beaches to dry. Once completely dried out the shells were ready to start their lives as currencies.

1200 B.C.: COWRIE SHELLS: The first use of cowries, the shells of a mollusk that was widely available in the shallow waters of the Pacific and Indian Oceans, was in China. Historically, many societies have used cowries as money, and even as recently as the middle of this century, cowries have been used in some parts of Africa. The cowrie is the most widely and longest used currency in history.

The largest part of this Maldive production was exported by local seamen to the main distribution centre of Bengal. Important question: what was the value of this commodity? The law of supply and demand, one of the basic laws of economics, played a dominant rôle. In areas far away from production or trade centers, a few cowries would buy a cow whereas in the Maldives itself a few hundred thousands equalled a gold dinar. Along the northeast trade route caravans of Arab traders introduced the cowry in the African inland but it were the Portugese, English, French and Dutch who promoted the cowry to the currency for commercial transactions, as e.g. trading in slaves, gold and other goods. The massive import of cowries along the African Westcoast however caused a few disruptions both sides of the trade route: whereas India had to deal with serious shortages in the 17th century local African currencies lost their values or even disappeared completely in favour of the cowries. The cowry continued to play its monetary rôle until the 20th century but the financial world has not completely turned its back on this popular currency. Its memory is, amongst others, kept alive in the façade of the Central Bank of West African Countries in Bamako, Mali or… in museums dedicated to money. (source: the National Bank of Belgium)

Cypraea moneta (cowrie)

Cowrie shells were the longest and most widely used currency of all times. In China they were circulating as money from the 2nd millennium BC. From there they spread over Thailand and Vietnam to the Indian subcontinent; finally they came into use also on the Philippines, the Maldives, in New Guinea, the South Seas and in Africa. On the African continent, cowrie money remained in circulation until the mid-20th century. Many cowries found on archeological sites are pierced like the specimen shown here, as they were also used for decorating clothes or tied together in strings for the payment of larger sums.

Shell Traders

Shell Traders from Willy Millard on Vimeo.