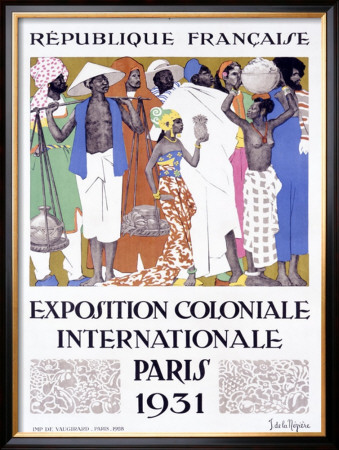

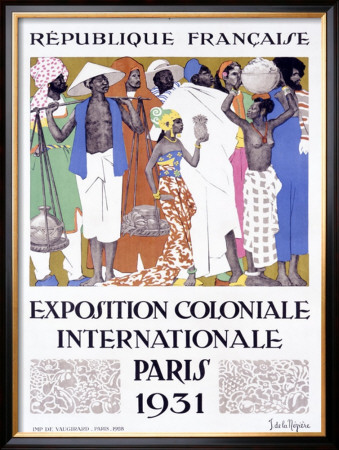

1931 - Visit to the Exposition Coloniale

On the corner of St. Louis and Chartres streets in 1838, the St. Louis hotel opened. It was also called the City Exchange Hotel. Two years later it burned down but was quickly rebuilt. The main entrance to the hotel led into the exchange, a beautiful domed rotunda where every afternoon between noon and 3 p.m. the auctions were held. In this elegant hotel, the center of Creole society before the Civil War, was located perhaps the most infamous of the slave auction blocks. There was more than one.

On the corner of St. Louis and Chartres streets in 1838, the St. Louis hotel opened. It was also called the City Exchange Hotel. Two years later it burned down but was quickly rebuilt. The main entrance to the hotel led into the exchange, a beautiful domed rotunda where every afternoon between noon and 3 p.m. the auctions were held. In this elegant hotel, the center of Creole society before the Civil War, was located perhaps the most infamous of the slave auction blocks. There was more than one.

Slaves were sold on this spot at the old St. Louis hotel, which had also served as the state Capitol and the site of Carnival balls. The hotel was on St. Louis between Chartres and Royal streets. Damaged in a 1915 storm, it was demolished two years later.

The luxurious Omni Royal Orleans hotel at the corner of St. Louis and Chartres streets stands on a site once home to a hotel rotunda that was the site of the city's most infamous slave-auction block.

Slaves in the upper South feared being sold into the lower South because of the harsh conditions and the hot climate. But hundreds of thousands of African Americans were forced to migrate South, tearing apart families. New Orleans became the center of the slave trade, especially after 1840, and the slave auction was one of the most cruel and inhumane practices of slavery.

Slaves in the upper South feared being sold into the lower South because of the harsh conditions and the hot climate. But hundreds of thousands of African Americans were forced to migrate South, tearing apart families. New Orleans became the center of the slave trade, especially after 1840, and the slave auction was one of the most cruel and inhumane practices of slavery.

Edict of the King:

On the subject of the Policy regarding the Islands of French America

March 1685

Recorded at the sovereign Council of Saint Domingue, 6 May 1687.

Louis, by the grace of God, King of France and Navarre: to all those here present and to those to come, GREETINGS. In that we must also care for all people that Divine Providence has put under our tutelage, we have agreed to have the reports of the officers we have sent to our American islands studied in our presence. These reports inform us of their need for our authority and our justice in order to maintain the discipline of the Roman, Catholic, and Apostolic Faith in the islands. Our authority is also required to settle issues dealing with the condition and quality of the slaves in said islands. We desire to settle these issues and inform them that, even though they reside infinitely far from our normal abode, we are always present for them, not only through the reach of our power but also by the promptness of our help toward their needs. For these reasons, and on the advice of our council and of our certain knowledge, absolute power and royal authority, we have declared, ruled, and ordered, and declare, rule, and order, that the following pleases us:

Article I. We desire and we expect that the Edict of 23 April 1615 of the late King, our most honored lord and father who remains glorious in our memory, be executed in our islands. This accomplished, we enjoin all of our officers to chase from our islands all the Jews who have established residence there. As with all declared enemies of Christianity, we command them to be gone within three months of the day of issuance of the present [order], at the risk of confiscation of their persons and their goods.

Article II. All slaves that shall be in our islands shall be baptized and instructed in the Roman, Catholic, and Apostolic Faith. We enjoin the inhabitants who shall purchase newly-arrived Negroes to inform the Governor and Intendant of said islands of this fact within no more that eight days, or risk being fined an arbitrary amount. They shall give the necessary orders to have them instructed and baptized within a suitable amount of time.

Article III. We forbid any religion other than the Roman, Catholic, and Apostolic Faith from being practiced in public. We desire that offenders be punished as rebels disobedient of our orders. We forbid any gathering to that end, which we declare to be conventicle, illegal, and seditious, and subject to the same punishment as would be applicable to the masters who permit it or accept it from their slaves.

Article IV. No persons assigned to positions of authority over Negroes shall be other than a member of the Roman, Catholic, and Apostolic Faith, and the master who assigned these persons shall risk having said Negroes confiscated, and arbitrary punishment levied against the persons who accepted said position of authority.